They're out there...and they're coming.

There’s a bumper crop of mosquitoes today. Might be one in the room with you, sitting on your shoulder like a tiny, weightless parrot. Do you know what kind of mosquito it is?

Who cares. A mosquito’s just a mosquito, right?

That’s like saying a bird’s just a bird. When you hear somebody say that, you think: no, that’s a male Red-winged Blackbird.

You’re not being a wise guy. You’ve just got a handle on the world around you.

Similarly, the mosquito on your shoulder is an Aedes vexans, Culex pipiens or Anopheles quadrimaculatus. Could even be an Uranotaenia sapphirina, a blue rarity.

Huh?

Are we really going into the arcane world of insects and Latin names? That would suck.

But still, in the interest of at least knowing what we don’t know, here’s a quick field guide to the mosquitoes. They’re not all the same. Once you know their names, you see them differently.

But, try to see them before they see you.

Floodwater mosquitoes

These are the “Aedes” family of mosquitoes. They lay eggs near water. When inundated, bam, population explosion. This is happening in my neighborhood right now.

Aedes in the Arctic have been known to swarm and kill caribou. Swarms like that don’t happen around here.

Aedes field markings: these guys are brown with striped abdomens. Bands of color on the legs, no wing spots. Their butts are pointy. Feelers are shorter than snouts.

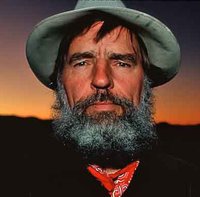

"Aedes vexans"

Some floodwater mosquitoes include: Aedes canadensis, the first sign of spring. Aedes stimulans, Aedes exrucians and Aedes fitchii. All are abundant, and bite even during daylight.

They say most Aedes can carry encephalitis, but Aedes triseriatus and Aedes trivittatus, identified by two bold stripes on the upper back are particularly known as carriers.

And there’s the common Aedes vexans, the one you’re likely to have around you. Experts say this mosquito will travel a mile for a meal. The ones hovering around my front door don’t want to travel that far.

When biting, Aedes mosquitoes get into a hunkered posture, head and tail angling down. This is another identification tip.

House mosquitoes

House mosquitoes are the Culex type, and you don’t want them in your house. They’re known for the diseases they carry, specifically West Nile Fever.

Culexes breed in stagnant water, old tires, beached boats, garbage cans and birdbaths.

In addition to West Nile, they can carry St. Louis encephalitis. Outbreaks of these diseases typically show up in late summer and make the TV news.

Culex field markings: drab brown, no wing spots. Body and leg bands are variable, sometimes faint, sometimes visible. Tails are squared-off.

A "Culex" house mosquito you don't want in the house

Culex pipiens is common, and rests during the day in houses (thus the name “house mosquito”). At night, they bite.

Culex restuans is active in spring and fall. They rarely bite people, but spread encephalitis in birds. Culex salinarius hangs around parks.

All Culex species are worth avoiding. Remove standing water. Don’t hike after dark. Use repellents. Arrange spraying. You’ve heard all this before.

Identification tip: When biting, Culexes hold their bodies parallel to your skin. This contrasts with the hunkered Aedes types, and especially with the next batch in our field guide.

Malaria mosquitoes

The mid-American version probably won’t carry malaria. But mosquitoes in this group, known as the Anopheles, have spread it in Illinois back in the early 1900s.

Anopheles quadrimaculatus, is a large, brown mosquito that lays eggs in clean ponds. Spotted wings are clear field markings.

"Anopheles" - The Malaria mosquito

And Anopheles mosquitoes have long feelers, same length as their snout. Aedes and Culex have shorter feelers. Mention that at your next beer blast.

Biting posture is, again, an I.D. tip: Anopheles mosquitoes tilt their bodies when biting, tails way up.

Tigers, speckle-wings and sapphires

The Asian tiger mosquito, Aedes albopictus, is an exotic, introduced accidentally when American truck tires had been sent to Asia to be recapped, and returned with stowaway eggs.

These mosquitoes can transmit dengue fever, but that’s not expected to be a problem here. More likely, just encephalitis or West Nile.

Asian "Tiger " mosquito. Not just in Asia any more.

Identification tip: Bold stripes. And they bite during daylight, making tiger mosquitoes easier to spot.

The speckled-wing mosquito, Psorophora columbiae is found near farms and feedlots. They’re mean biters.

Finally, the “collectors item:” Uranotaenia sapphirina. An iridescent blue specimen that breeds in ponds. They’re non-aggressive and not often seen. They’re “rare birds.”

Mosquitoes have survived for 50 million years. We’ve only been talking about them a couple of minutes here. For some of us, that too, has been a survival story.

When it comes to identifying the things that fly, we’ll stick with birds.