The following, more or less, ran in this Viewpoints column a while back. Let’s see what we were writing and reading then. When, exactly? Fourth of July…fourteen years ago!

What does two-fisted birdwatching have to do with science fiction? Two things: Not much. And a lot.

Not much…

Two-fisted birdwatching is about getting into the rugged, buggy, woodsy, overgrown, muddy wilderness. It’s about sometimes seeing bears and liking it. It’s about seeing birds, and knowing their names. It’s about going places alone, getting lost, scratched by thorns, and spending some time like you’re living on the frontier.

Two-fisted birdwatching has not much to do with time travel, UFOs, lost-world dinosaurs and leaps of imagination. Wait a second. Did we just say time travel…? Hold on.

A lot…

Two-fisted birdwatching is about time travel. And this rugged sport is also about dinosaurs, unidentified flying objects and imagination. Walk in the suburban wilds today, and you could be in a time machine. When no jet contrails are ruining the sky, it could be the 1800s, the 1600s, hell, it could be twenty thousand years ago. The place belongs to trees, bugs, animals and birds.

Walk the game trails. As long as you avoid human hikers, you’re living apart from time as we know it. It’s just “place.” And “time” is taking the day off. If that sounds like science fiction, well, cool.

And then there are dinosaurs! The latest information, including a story in National Geographic, reports that birds didn’t descend from dinosaurs; they are dinosaurs.

Look into the eyes of a Great Blue Heron if you can get close. Millions of years of saurian self-confidence will stare back at you. Look at the scaly claws, the bone structure. Birds equal dinosaurs. A classic sci-fi subject. Next: “Unidentified flying objects.” Do we really have to say more?

One final point: imagination. When you walk in the woods, your two fists wrapped around grubby binoculars, you think of things. You’re not always spotting birds. You think up stories. Sometimes they’re science fiction stories. Take a look at “The Ferruginous Hawk.” It came from the imagination of a guy walking in a birdless woods on a birdless day.

“Independence Day.”

Today is July 4th. Independence Day. That’s also the title of a classic sci-fi movie. We might re-watch it tonight. We like science fiction. And people who like it, too.

Sometimes science fiction fans are believed to be a little nerdy. An unfair image problem. Actually, they’re generally bright and interesting.

Sometimes science fiction fans are believed to be a little nerdy. An unfair image problem. Actually, they’re generally bright and interesting.

The public imagination has also thought of bird watchers as a little nerdy, too. Screw the public imagination. Two-fisted birdwatching zaps that image into another dimension.

You’ll keep going into wild places, and these places will be time machines. With flying dinosaurs you’ll identify and some that will remain UFOs. And, as you go where no one has gone before, you’ll know that your style of birdwatching has not much in common with sci-fi stories. And also a lot in common.

That sounds like a paradox. All the best time travel adventures are paradoxes.

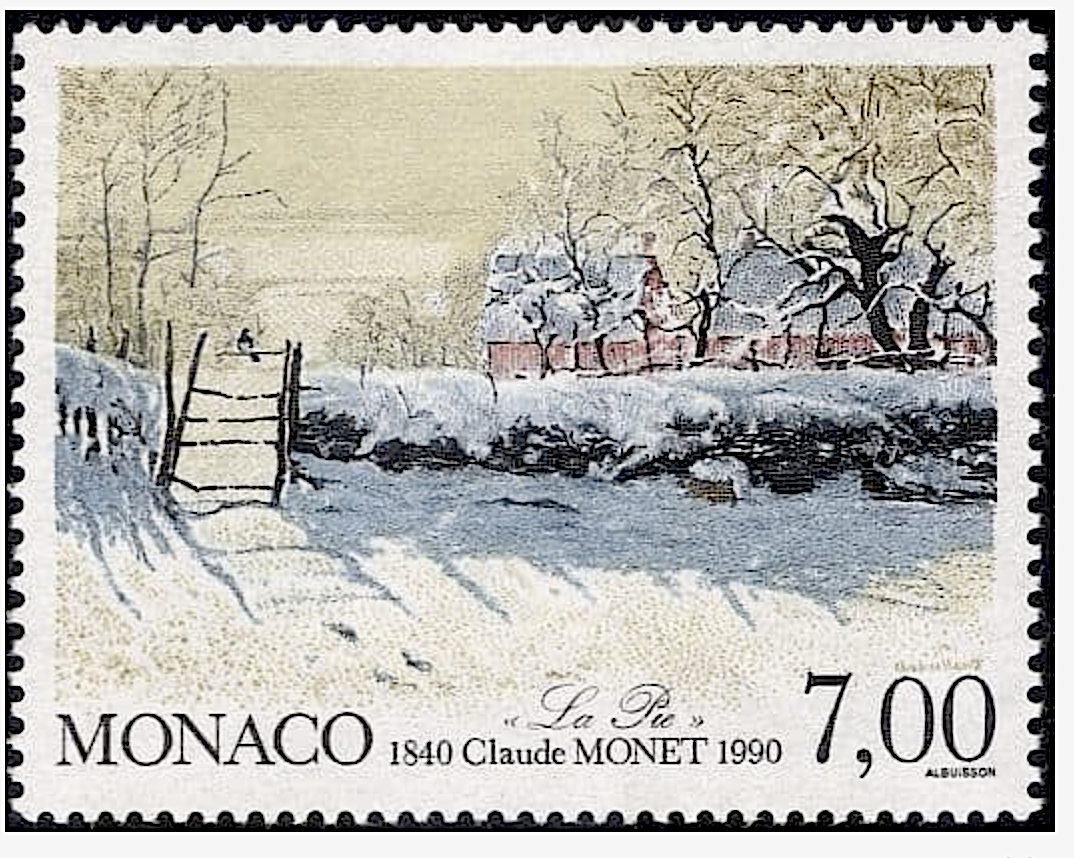

Apparently the country of Monaco thought so much of this awesomely titled painting that they put it on one of their postage stamps. You saw it recently, and it stopped you cold.

Apparently the country of Monaco thought so much of this awesomely titled painting that they put it on one of their postage stamps. You saw it recently, and it stopped you cold.