If you ever visit the website, North American Birding (nabirding.com), you’ll come across articles occasionally contributed by “Mike at Two-Fisted Birdwatcher.” That name might ring a bell.

Don’t laugh at the photo that goes with these stories. Yeah, it’s me, a few years younger and a whole lot hairier.

I wrote the following piece specifically for North American Birding, and it ran there November 6, 2010. The subject continues to be interesting, especially with the recent publication of Edmund Morris’s “Colonel Roosevelt,” an excellent if overlong finale to his trilogy.

It’s about a guy who I believe was our first two-fisted birdwatcher. Biographers report that he cold-cocked a gun-waving cowboy in a saloon in Dakota territory with two punches.

And we know he was a bird watcher because he wrote and published field guides. He knew birds and their calls like a pro. But there was more to him than fists and birds…

“The ornithologist who started a war.”

I saw a sign on my hike this morning. It said: “dedicated nature preserve.” I also saw a Fox Sparrow.

Those two things got me thinking about a nerd who changed his image and started a major war.

This guy’s more interesting than the Hairy Woodpecker, Red-bellied Woodpecker, Dark-eyed Juncos and the shivering late-season Eastern Bluebird that I also saw.

The sign reminded me of him because he started a conservation movement resulting in national parks and bird sanctuaries.

The Fox Sparrow reminded me of him, because he knew one when he saw it, and even when he didn’t. We’ll get to that, but first…

If you think bird watchers have been saddled with a nerdy image in your lifetime, imagine what it must’ve been like to have that interest in 1870s America.

Then imagine that the bird watcher in question was a scrawny, squeaky voiced little guy with ever-present spectacles. The age-old image of a four-eyed dweeb.

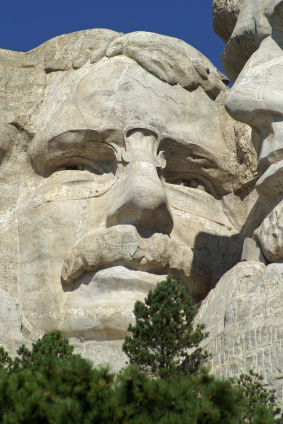

The guy is young Theodore Roosevelt. Not Franklin Roosevelt; people get them confused. This is Theodore, who lived in the late 1800s and early 1900s.

Talk about a complicated character. He’s a textbook case of overcompensation. But sometimes overcompensation works. Roosevelt’s weak and sickly start in life turned him into a gutsy guy who did everything to become a he-man.

Two facts are interesting here, for us, at least.

The guy was an avid bird nut. A true ornithologist. He wrote extensively on the subject: “Summer Birds of the Adirondacks,” “Notes on Some of the Birds of Oyster Bay, New York,” even a tract in 1910 called “English Songbirds.”

A few years later in life, when he was attacking Spanish troops in Cuba with his cowboy band of “rough riders,” he noticed calls of wood doves and a mysterious Cuban cuckoo. These turned out to be Spanish snipers signaling each other. The snipers were discovered and routed. Did Roosevelt know the bird calls were bogus?

How did this bird geek grow up to start a war?

When he wasn’t bird watching or writing about birds, he was doing other things. His friend Henry Adams called him “pure act.” Roosevelt was driven and tireless.

He succeeded at Harvard. Got married twice, had a bunch of kids, did ranching and cow-punching in Dakota Territory, researched naval history and wrote a landmark book about it, then became a big shot in various political jobs. And, as you know, he was president of the United States from 1901 to 1909.

But before that he pulled strings to get a post as Assistant Secretary of the Navy under a reputedly lazy old guy who vacationed a lot, leaving Roosevelt in charge.

Young Roosevelt single-handedly built up the navy during this period, and when a small revolt in Cuba caught his eye, he saw it as an opportunity to make America a badass good-guy on the world stage. He personally manipulated people and events to bring about the Spanish-American War.

Could one man single-handedly influence global powers to go to war? Quick answer: if it’s this ornithologist, yeah. For details, check out Edmund Morris’s “The Rise of Theodore Roosevelt.”

But the point of all this is that here’s a skinny, bespectacled birdwatcher, and he grew into a brawny bespectacled warrior, cowboy, U.S. president, jungle explorer (see “The River of Doubt” by Candice Millard; incredible!), creator of our national park system, 150 National Forests, 51 Federal Bird Reservations, and he most likely set the stage for the Pacific war with Japan long after he was gone (see “The Imperial Cruise,” by James Bradley).

He liked to say “bully” meaning “good,” and he might have been a different kind of bully; leave that to the historians. But he was a bird watcher to the last.

As a big-bellied old guy walking around the White House lawn toward the end of his presidency, he picked up a tiny bit of fuzz and commented, “Hmm, a feather from a Fox Sparrow.”

From matters of state and matters of war…to matters of wildlife preserves like the one I visited this morning… to matters of sparrow species, that was Theodore Roosevelt. A two-fisted birdwatcher if there ever was one.

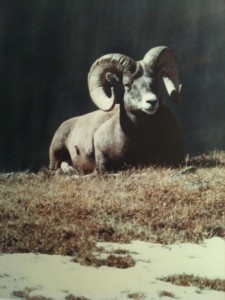

I also saw a Mountain Bluebird that day, another first. I took its picture.

I also saw a Mountain Bluebird that day, another first. I took its picture.